| Medical Center | Strong Memorial

Hospital and School of Medicine and Dentistry |

|

| Strong Memorial Hospital and School of Medicine and Dentistry in November 1933 |

|

|

|

|

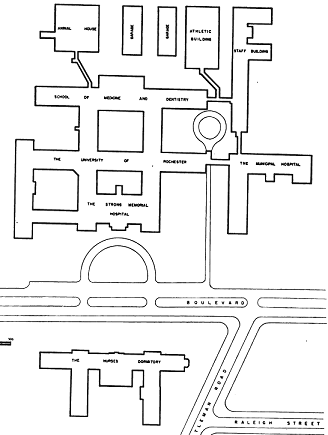

| Plot Plan from Hospital

Planning, by Charles Butler and Addison Erdman (1946) Page 118 |

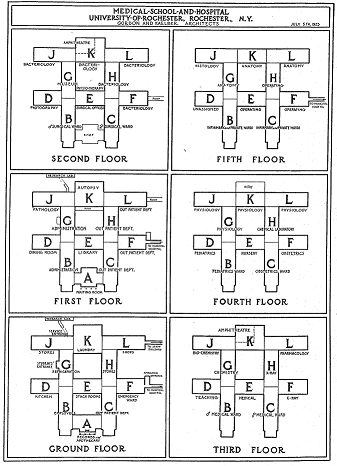

Floor Plan of Building, July 1923 |

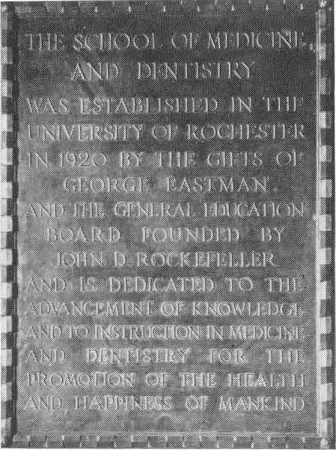

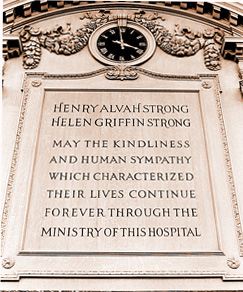

Plaque honoring George Eastman and John D. Rockefeller | Plaque honoring Henry Alvah Strong and Helen Griffin Strong |

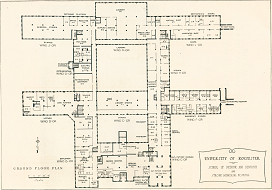

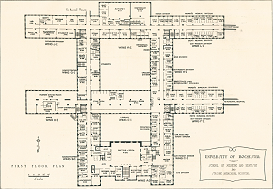

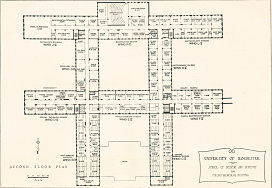

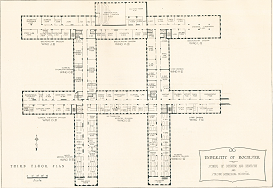

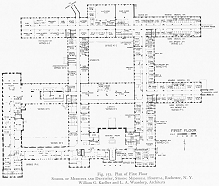

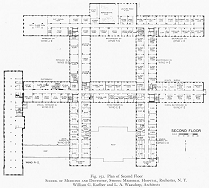

| 1926 Floor

Plans from Methods and Problems of

Medical Education, Series Seven (1927) Pages 2-7. Click on images for larger version |

||

|

|

|

| Ground Floor |

First Floor |

Second Floor |

|

|

|

| Third Floor |

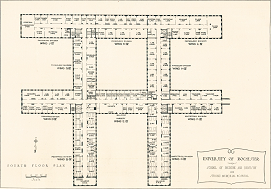

Fourth Floor |

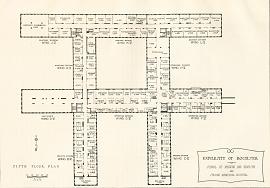

Fifth Floor |

| 1946 Floor

Plans from Hospital

Planning, by Charles Butler and Addison Erdman (1946)

Pages 119-124. Note that these plans include the 1941

Wing. Click on images for larger version |

||

|

|

|

| Ground Floor |

First Floor |

Second Floor |

|

|

|

| Third Floor |

Fourth Floor |

Fifth Floor |

Once the property was purchased, planning for the new Medical Center led to a decision to house the Medical School and Hospital under one roof, which was the first time this had been done. A two-story research building opened in November 1922 while architects worked with George Eastman and the School's faculty to design the new building. By July 1923 a schematic was prepared showing building with two north-sound and three east-west elements divided into several wings identified by letters. The southern part of the building would hospital space and the northern for the Medical School. The City of Rochester's new Municipal Hospital would be connected to the east end of the hospital and consist of two additional wings, to be named 'X' and 'Y'. Added wings were also given letter designations until the construction of the new Strong Hospital in 1975, at which time the entire complex was renumbered with lower numbers in the southeast corners and higher numbers to the north and west.

Construction began in August 1923 and a rail spur was built from the Lehigh Valley Railroad tracks to deliver material. This spur ran parallel to the trolley tracks in Crittenden Bouldvard and was removed after the building was completed. A cornerstone ceremony was held on June 14, 1924. Steam was delivered to the building in November from the new heating plant and in January the Biochemisry department moved out of the Animal House into the new J Wing and President Rhees addressed their first seminar on January 21, 1925. The first students arrived in September 1925 and Strong Memorial Hospital opened on January 4, 1926. The building had six floors with the exception of a half-width floor for offices on top of E Wing (now 6-6200). The basement was unfinished (with a few exceptions) and was primarily used to route pipes and wires under the building. Whipple later wrote that "the most serious mistake that was made in designing the main plant which should have had a full-sized finished basement, beneath the ground floor level," All later additions had full finished basements.

The building included triangle-shaped concrete curbs in some hallways to prevent damage to walls from gurneys and carts, as shown below:

|

The corners of the stair towers were painted white to discourage spitting chewing tobacco.

Whipple did now allow Blacks to enroll in the Medical School, and few, if any, Jews or Asians were admitted. A 1939 report by The Temporary Commission on the Condition of the Colored Urban Population pointed out that such discrimination violated the state's tax laws and could result in revocation of the school's tax-exempt status. Whipple allowed one Black student to enter in 1940 (Edwin A. Robinson, who graduated in December 1943), and a handful over the remaining 15 years of his tenure as dean. His old office was maintained as a museum until 2020, when it was emptied and repurposed as a Wellness Room after he was cancelled for his racist views.

Several new wings were added to the original building starting in 1941 and the University took possession of the Rochester Municipal Hospital on July 1, 1963. Laundry facilities were provided in the original building, but were outsourced in 1964 to a cooperative of local hospitals, Aid to Hospitals, Inc.

The interior spaces of the original building have been renovated numerous times it was constructed, but only a few exterior changes have been made, including the 1962 and 1987 Miner Library expansions, and the Alastair J. Gillies Anesthesiology Library on top of L Wing (6-5436) in the mid-1980s. The G-5200 area was infilled in 2003 for Surgical Pathology.

With the opening of the new Strong Memorial Hospital in 1975, the fully-depreciated hospital portion of the old building was transferred to the School of Medicine and Dentistry.

References

1919 "Henry

A. Strong, Long Business Associates of George Eastman, Dead in his

Eighty-First Year," Democrat and Chronicle, July 27, 1919,

page 38.

1920 "Gift of $9,000,000 to University by Eastman and Rockefeller for School of Medicine Announced," Democrat and Chronicle, June 12, 1920, Page 1. | Part 2 | Part 3 |

1921 "To Make Trip in Interest of New Medical School," Democrat and Chronicle, January 4, 1921, Page 16.

1921 "Million

Dollars is Given by Two Women for Hospital for University's Medical

School," Democrat and Chronicle, February 25, 1921, Page 21.

Daughters of Late Henry A. Strong Donors. Great Sum to be Used in

Erection of Memorial to Their Parents.

1921 "University of California Man is Appointed Dean of University Medical School," Democrat and Chronicle, April 2, 1921, Page 25.

1921 "The

Medical College," Democrat and Chronicle, October 6, 1921,

Page 10.

The man who will run that school is George Hoyt Whipple.

1921 "Oak

Hill Site Is Approved by University Trustees," Democrat and

Chronicle, November 6, 1921, Page 1. | Part

2 |

Present Plan Would Place College For Men on Country Club Site and Medical

School on Elmwood Avenue.

1923 Medical School and Hospital, University of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y., by Gordon and Kaelber, Architects, July 5, 1923.

1924 "The Medical School of the University of Rochester," Science, New Series 59(1519):140 (February 8, 1924)

1924 "Huge Plant of New Medical School Rises Against Skyline," Democrat and Chronicle, October 27, 1924, Page 20. | part 2 |

1925 "U.R.

Medical College Nears Completion," Democrat and Chronicle,

May 25, 1925, Page 21.

Nurses' Dormitories to Be Ready for Occupancy in September.

1925 "University

Rushing Construction Work on New and Old Campuses," Democrat and

Chronicle, July 19, 1925, Page 32.

Art Gallery, Dormitory and Medical School Works Progressing.

1925 "U.R. Medical School Opens This Morning," Democrat and Chronicle, September 17, 1925, Page 17. | Part 2 |

1926 "New Hospital Opens Doors; One Patient," Democrat and Chronicle, January 5, 1926, Page 15.

1925 "U.R.

Medical College Nears Completion," Democrat and Chronicle,

May 25, 1925, Page 21.

Nurses' Dormitories to Be Ready for Occupancy in September.

1926 "Strong

Hospital Opens; Four Clinics are Active," The Campus,

February 19, 1926, Page 4.

The first patient was received Monday at the Strong Memorial Hospital.

1926 "Medical School Dedication Interests World of Science," Democrat and Chronicle, October 24, 1926, Page 1. | Part 2 |

1927 Methods

and Problems of Medical Education, Series Seven, Division of

Medical Education of the Rockefeller Foundation, February 17, 1927.

Composed of descriptions of the new school of Medicine and Dentistry of

the University of Rochester, at Rochester, New York

Pages 1-14: School and Hospital Plans, by George Hoyt Whipple

Pages 15-19: Animal House, by George Hoyt Whipple

Pages 21-28: Department of Anatomy, by George W. Corner

Pages 29-35: Department of Physiology, by Wallace O. Fenn

Pages 37-43: Department of Biochemistry and Pharmacology, by Walter Ray

Bloor

Pages 45-53: Department of Vital Economics, by John R. Murlin

Pages 55-60: Department of Pathology, by George Hoyt Whipple

Pages 61-66: Department of Bacteriology, by Stanhope Bayne-Jones

Pages 67-73: Department of Medicine, by William S. McCann

Pages 75-81: Department of Pediatrics, by Samuel Wolcott Clausen

Pages 83-90: Department of Surgery, by John L. Morton, Jr. .

Pages 91-94: Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, by Karl M. Wilson

1927 "Rochester's New Medical Group - An Example of Progress," by Nathaniel W. Faxon, The Modern Hospital 29(5):53-61 (November 1927) | reprint |

1929 "Woman

dies as car goes into ditch," Democrat and Chronicle,

February 25, 1929, Page 1.

Mrs. Albert Dunson, 43, of 471 Mount Hope Avenue, secretary to Dr. George

H. Whipple, dean of the Medical School of the University of Rochester, was

instantly killed early yesterday morning when the light roadster in which

she was riding ran off the West Henrietta Road on the north side of

Methodist Hill, crashed through a guard rail and dropped into a ditch

where it was wrecked.

1929 "100

Killed when Cleveland blast spreads poison gas," Democrat and

Chronicle, May 16, 1929, Page 1.

Stored X-ray films blaze; people in street overcome.

1934 "Nobel

Prize Shared by Dr. Whipple," Democrat and Chronicle,

October 26, 1934, Page 1 | Part

2 |

In his work here he had the assistance of Mrs.

Frieda S. Robbins, physiologist.

1936 The First Decade 1926-1936

1939 "Prexy

Denies Discrimination Against Negroes," The Campus, January

13, 1939, Page 1 | Part

2 |

Medical School hit for racial ban; U. of R. blames society.

1939 Second Report of

the New York State Temporary Commission on the Condition of the Colored

Urban Population, February 1939, Legislative Document No. 69 (1939)

Pages 114-115: Medical Schools - Hospitals

Perhaps the boldest example of such discrimination against Negroes is

indicated in the letter which the Dean of the School of Medicine and

Dentistry of the University of Rochester sends to Negro applicants. The

letter reads as follows:

The Admission Committee on several occasions has discussed carefully with the President the question of Negro students in this school of medicine. It is possible for this school to give the work of the first two years, but it would be impossible for us to offer clinical training, particularly in obstetrics, which is of fundamental importance in the clinical curriculum. Under the circumstances, therefore, we feel that it would be much wiser for you to apply to several of the schools who can, and do, give adequate clinical training to Negro students. The transfer from a completed second year to another school is always difficult so that it is better to enroll in the school in which the student plans to carry through the entire four years.

This letter has been most

effective in excluding Negro students, for although there have been many

applicants, there has never been a Negro medical student at that school.

At the Rochester public hearings conducted by the Commission, the dean of

the school and director of the hospital stated that it was their belief

that admission of Negroes to the medical school and nurses' training

school would cause wholesale objection on the part of white patients in

the hospital where they practice, would cause the white students to quit

instantly and would cause a serious disrupting of the entire program of

the hospital. They admitted that they actually based their assumption on

no practical experience and that they were not acquainted with the fact

that Negroes attend many university medical schools, other than those of

Negro colleges and universities. When informed of the fact that a Negro

woman had been admitted to the Nurses' Training School of the Buffalo

Municipal Hospital, not very far from Rochester, and that not one student

nurse had resigned or even voiced an objection, these officials could do

no more than shrug their shoulders. And, when confronted with the

testimony that in the City of Rochester itself there were three Negro

physicians whose practices were 60 per cent, 75 per cent and 95 per cent

white-involving all types of cases including obstetrics-these officials

were at a loss for a reasonable explanation of their opinions. Obviously

these were simply conjectures, and the entire situation is an example of

flaunted discrimination against Negroes-in violation of the Civil Rights

Law and the Tax Law of the State of New York.

1939 "State

Commission Charges Widespread Racial Discrimination Practiced," Democrat

and Chronicle, February 27, 1939, Page 4.

Group to present measures to aid Negro.

4. Prohibit discrimination in any housing project and regulate

procedure for educational institution admission to assure that applicants

shall not be excluded because of race, color or creed.

5. Withdraw tax exemptions from education institutions which deny use of

their facilities because of rice or color, and suspend or revoke the

license of any public place of accommodation denying equal facilities or

privileges.

1940 "For Sale 30 Ton Ice Plant," Democrat and Chronicle, July 7, 1940, Page 19.

1941 "Naval Hospital Unit Formed at U. of R. Medical School," Democrat and Chronicle, February 28, 1941, Page 18.

1946 Hospital

Planning, by Charles Butler and Addison Erdman

Pages 118-128: Strong Memorial Hospital and Rochester Municipal

Hospital, including floor plans

1950 The First Quarter Century 1925-1950

1953 "Jewish Congress Sees School Discrimination," Democrat and Chronicle, June 23, 1953, Page 3.

1957 Planning

and Construction Period of the School and Hospitals 1921-1925.

bu George H. Whipple, M.D.| pdf |

Pages 15-16: Mr. Eastman was an expert in the prevention of

disasters relating to explosive and inflammable materials and one of his

first suggestions related to the water supply of the main plant. As

originally planned, there was a single intake pipe of some size from a

water main in Crittenden Boulevard. Mr. Eastman said that the whole plant

should be surrounded by a sizable water main with suitable valves and at

least two, and preferably three or four, separate connections with city

water mains. This would mean that, no matter what accident might occur

relative to pipes or valves, a water supply under necessary pressure would

be available against any emergency. That general arrangement with three

separate intake lines is complete at this time.

As he looked over the long corridors running through several departments

and hospital wards, as well as some chemical and some experimental

laboratories in which were used inflammable chemicals oftentimes of

explosive nature, he stated emphatically that these long corridors should

be broken up into units of approximately 100 feet by fire doors at

suitable places in these corridors. After careful study, heavy brickwork

and metal doors were placed at strategic locations. When this general

program was outlined, the cost of these fire-door installations amounted

to many thousands of dollars and the question was therefore raised with

Mr. Eastman as to whether this insurance could be justified. His reply was

to the effect that if, during the use of the plant over the foreseeable

future, a single dangerous explosion which might cost the life of one or

more persons was prevented or contained, then the cost was amply

justified. No argument could be aimed against this clear statement and the

fire doors are in place and give additional security.

When Mr. Eastman saw the layout of the X-ray Department, he realized that

there would be a great deal of film which would require storage for

reference purposes as a part of the history of the sick patients over the

years. He gave study to the storeroom as outlined on the blueprints and

found it inadequate in several respects. There was a small vent shaft

similar to that found in most of the laboratories and storerooms. He

pointed out that there was need for more space, but above everything else

there should be a large free vent going straight up through the upper

floors and roof so that if explosion or fire developed, these films would

not endanger that area and the fumes would escape freely to the open air.

The vent measures three by two feet.

When the catastrophe due to burning films in the X-ray storage room hit

the great Cleveland Hospital (Crile Clinic) in 1929, these poisonous fumes

killed 223 persons in the hospital and of course aroused criticism all

over the nation. After that event, every reputable hospital was reviewed

by the faculty, physicians, fire underwriters and others to avert any such

catastrophe in the future. The Strong Memorial Hospital was the only one

where the underwriters could find nothing to suggest to improve conditions

except perhaps to make the room a little larger.

1958 "Interfaith Chapel Planned at Strong Hospital," Democrat and Chronicle, February 23, 1958, Page 34.

1959 "Autobiographical

Sketch," by George Hoyt Whipple, Perspectives in Biology and

Medicine 2(3):253-289 (Spring 1959)

Pages 274-275: As blueprints began to flow from the architect's office, we

had many pleasant discussions with Mr. Eastman. He said many times that

plenty of medical schools and universities had demonstrated how much could

be spent on construction, exterior adornment, and interior furnishings;

for his part, he would like to see how little could be spent while

assuring ex-ceilence of construction and function. The architects

naturally wished the new structure to be a monument and memorial. The

trustees and others participated in the debate, which became lively and,

at times, a bit warm. The simple type of building was branded as

"Late Penitentiary," "Factory type," and so on. President Rhees took a

neutral stand. Finally, Mr. Eastman took a firm stand for simplicity and

settled the debate with Mr. Lawrence White, the consulting architect. I

was happy at this decision, as I had worked in very simple buildings at

Hopkins and at the Hooper Foundation and knew that such laboratories were

satisfactory and that the upkeep was minimal. The savings from proposed

exterior decorations of the main buildings alone were of the order of one

to two million plus inevitable delay.

Mr. Eastman was sincerely interested in the blueprints as they took

form. He never looked at them without making constructive

suggestions, as described elsewhere. He was an expert in the prevention of

explosions and fires in industrial buildings (film manufacture, Eastman

Kodak Company) and suggested invaluable protective devices for the school

and hospital plant.

1960 Abraham

Flexner: An Autobiography

Page 151: Looking back over the last quarter of a century, one

cannot but be struck by the fact that the great, strong colleges and

universities of today were, a relatively short time ago, small

colleges. A striking example is the University of Rochester, which

had assets of about $4,000,000 in 1920, when the General Education Board

became interested in assisting it to establish a modern medical school in

northern New York. Within a few years persons who had had no conception of

the possibilities of the institution had become so deeply interested in it

that its endowment increased from $4,000,000 to $44,000,000.

Pages 180-185: Chapter 17: George

Eastman

1963 "Hang Out the Wash,"

University Record 3(6):4-5 (June 1963)

Situated just beyond the surgical emergency department, the laundry

provides the hospital as well as the Medical Center with over 180 separate

clean, pressed articles, including everything from heavy blankets to small

squares of cloth used as wrappers for fine surgical instruments. As Jack

Brignall, laundry manager commented, “without us the hospital and Medical

Center would find it difficult to function properly.” Jack, who is

entering his tenth year of service with the University, has been manager

of the laundry since 1961, and has progressed from mowing lawns for

Physical Plant to his present position.

With 41 full-time and 25 part-time employees, the SMH laundry can process

12,000 to 15,000 pounds of soiled laundry daily, or enough sheets to meet

the needs of the average family of four for a year. This would keep the

same family in towels and pillow cases for two years.

1963 George

Hoyt Whipple and his Friends: The Life-Story of a Nobel Prize

Pathologist, by George W. Corner

Pages 299-321: Bibliography of Whipple's publications

1965 "SMH Mobilizes,

Averts Disaster," University Record. 5(10):6 (November 1965)

A month after Strong Memorial Hospital’s disaster drill (see center

spread), a real crisis suddenly struck. On Tuesday, Nov. 9, Rochester

along with the whole Northeast was plunged into blackness from a massive

electrical power failure.

Among the first fearful thoughts that enter a person’s mind in such a

situation is, “What about the hospitals? What will they do?”

1966 "New Facility for

Linen Being Built," University Record 4(6):3 (June 1966)

A temporary linen handling facility now under construction beside the S

& A Building will, when completed around Aug. 1, serve as the

clearinghouse between Strong Memorial Hospital and the new centralized

laundry at Buffalo and McKee Roads.

The centralized laundry will open this summer to serve five Rochester

hospitals, including Strong. At that time the present laundry in Strong

will be closed down.

This facility will receive soiled linen from the hospital and send it on

to the centralized laundry, then distribute the clean linen throughout the

hospital when it comes back.

A1 Fioravanti, construction engineer for the Medical Center, said the

facility would be a 60-ft. by 100-ft. prefabricated metal building. It

will be olive green with white trim, “and quite attractive,” he added.

A receiving dock, covered by a 12-ft. canopy, will extend along the

building’s 60-ft. width between the east wall of the S & A Building

and the tennis courts.

1967 "New Quarters for Emergency Department," University Record 7(10):1 (November 1967)

1975 To

each his farthest star: The University of Rochester Medical

Center -1925-1975, edited by Edward C. Atwater and John

Romano.

Page 52: Another striking example of Dean Whipple's liberality was

the absence of locks from laboratory doors. Staff and students alike were

free to come at any time, day or night, as they wished. It was not

uncommon to find people at work late into the night, or groups of students

deep in conversation with a young instructor.

Page 60: In the early years most rooms in the School and hospitals

had no locks on the doors. Losses by pilferage were much less than the

projected cost, in time as well as money, for installation of locks on the

1,250 doors.

The Hospital elevators required operators, who worked a lever to start and

stop the motor. Elevator men befriended visitors and saw to it that none

got lost. Time-saving then was not the chief concern of either elevator

operators or their employer.

Page 480-481: Plans for the new School-Hospital were carefully

reviewed by George Eastman, who wanted to see the community get the best

interest on his investment. Early drawings of Gordon and Kaelber didn't

satisfy him. He was interested in utilitarian, rather than artistic,

features. He invited one of the architects to accompany him to Kodak Park,

where he pointed out a factory building as his model of a hospital. He

wanted "no fancy stuff."

He paid much attention to fire protection and accident prevention. That

the building had exposed pipes and was labeled by some critics as "early

penitentiary" architecture didn't bother him. But a Cleveland Clinic or

Hartford Hospital fire with heavy loss of life, which came later, would

have devastated him.

An ugly temporary two-story $60,000 research building and animal house,

facing Elmwood Avenue, was the first structure to arise in 1922, four

years before the opening of the Medical Center. It was occupied by Dr.

Whipple and several hundreds of animals. There the new dean continued the

research on blood-building liver extracts that led to the alleviation of

pernicious anemia, which gave him the Nobel Prize in 1934.

1976 George Hoyt Whipple (1878-1976) grave in Mt. Hope Cemetery

1976 "Dr. George H. Whipple, medical pioneer, dies," Democrat and Chronicle, February 2, 1976, Page 1B. | Part 2 |

1977 George Hoyt Whipple, 1878-1976 : recollections of his students at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, by University of Rochester. Medical Center. Alumni Association.

1977 History

of the University of Rochester, 1850-1962, by Arthur J.

May. Expanded edition with notes

Chapter 20, Shaping the Medical Center

Chapter 28: Music and Medicine in the 1930's

Chapter 31: Women, Music and Medicine in Wartime

1981 "George H Whipple or How to Be a Great Man Without Knowing Differential Equations," by Horace.W. Davenport, The Physiologist 24(2):1-5 1981, p. 2

1995 "George Hoyt Whipple, 1878-1976 : a biographical memoir," by Leon L. Miller, Biographical memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences 66:371-393 (1995)

2007 Dictionary

of Women Worldwide 2:1016

Robscheit-Robbins, Frieda (1888–1973)

American pathologist. Name variations: Frieda Sprague. Born June 8, 1888,

in Germany; died Dec 1973 in Tucson, Arizona; University of Chicago, BS;

University of California, MS; University of Rochester, PhD; married O.V.

Sprague.

Moved to US when young; began working with George Whipple at University of

Rochester (1917) and remained his research partner for 18 years; with

Whipple, conducted research on iron metabolism, discovering factors which

cause pernicious anemia, and the usefulness of liver therapy in treatment

of the disease; published 21 papers with Whipple (1925–30); was passed

over for Nobel Prize (1934), which was awarded to Whipple, though he did

share prize money; after Whipple's death, continued research until

retirement (1955), still only an associate professor.

2012 “Modernizing the American medical school, 1893-1940: architecture, pedagogy, professionalization, and philanthropy,” by Katherine L. Carroll, PhD Dissertation, Boston University

2016 "Creating

the Modern Physician: The Architecture of American Medical Schools in

the Era of Medical Education Reform," Katherine L. Carroll, Journal

of the Society of Architectural Historians 75(1):48-73 (March 2016)

Page 71, Note 56: After his work at the Carnegie Foundation, Flexner

became the leader of the medical education program of John D.

Rockefeller’s General Edu-cation Board, where he

worked from 1912 to 1928. In

this role, Flexner helped to enact the system of medical

education outlined in his 1910 report and focused the

board’s financial resources on the

medical college at the University of

Rochester rather than on the medical

school at Syracuse University. For a

larger analysis of Syracuse’s efforts

to obtain funding through the General

Education Board, including Flexner’s role

in chan-neling money to Rochester

rather than to Syracuse, see Carroll,

“Modernizing the American Medical School,”

202–6. For a thorough study of

Flexner’s development of a national program for medical education and his

implementation of this program through his work at the General Education

Board, see Steven C. Wheatley, The Politics of Philanthropy: Abraham

Flexner and Medical Education

(Madison: University of Wisconsin Press,

1989), esp. chaps. 3–5, on the rise and fall of Flexner’s management

system.

2016 "What

will it take? Fulfilling the promise of diversity in medicine,"

Rochester Medicine 2:18-49 (2016)

Page 21: The first class of students admitted to the University of

Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry in 1925 consisted of twenty men

and two women, all white, and all hand-selected by dean George Whipple,

MD. Notorious for his anti-Semitism and unabashed bigotry toward

African-Americans, Whipple systematically excluded students based on race

and religion until 1940, when the New York State Legislative Commission

threatened to take away the school’s tax exemption status if it did not

open its doors to all. For years later, only one African-American

male was admitted per class, until more conscious efforts to diversify the

student body began in the 1970s. While the URSMD was not unlike many

other predominantly white medical schools in its discriminatory practices,

it bears the burden of a tarnished legacy of racism nonetheless. For

decades, URMC’s Strong Memorial Hospital, which had separate white and

black nurseries until they were abolished in the 1960s, was perceived as

the “white hospital” serving predominantly white, wealthy residents, while

Rochester General (formerly known as Northside) Hospital, tended more to

the city’s poorer, black communities.

2017 "From the Editor," by Christine Roth, Rochester Medicine 1:6-7 (2017)

2020 "'The

time has come," Democrat and Chronicle, June 19, 2020, Page

A1. | Part

2 |

Symbolic gesture is part of URMC's pledge to confront failings about race.

Without fanfare or public notice, the University of Rochester this week

began stripping the name of its founder from public spaces on campus.

First to go was the sign memorializing his former office at the George Hoyt

Whipple Museum. “The time has come,” Dr. Mark Taubman, the center’s

current CEO and dean of the School of Medicine and Dentistry, wrote in a

letter to student activists who have presented the school with lists of

demands for greater equity and racial sensitivity. One of those demands

was taking down tributes to Whipple, a Nobel laureate and the first dean of

the medical school, who resisted pressure to admit black students,

reportedly allowing one per class only after being threatened with loss of

funding and nonprofit status. His office will be emptied, and repurposed as a

multicultural space. Taubman also announced creation of two full-ride

scholarships for yet-to-commit Black students in the upcoming class.

2020 Atomic Doctors: Conscience and Complicity at the Dawn of the Nuclear Age, by James L. Nolan

2022 Building Schools, Making Doctors: Architecture and the Coming of Age of American Physicians, by Katherine L. Carroll, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022 (forthcoming)

2024 Examining the Past: The Struggle for Racial Equality at URMC

© 2021 Morris A. Pierce