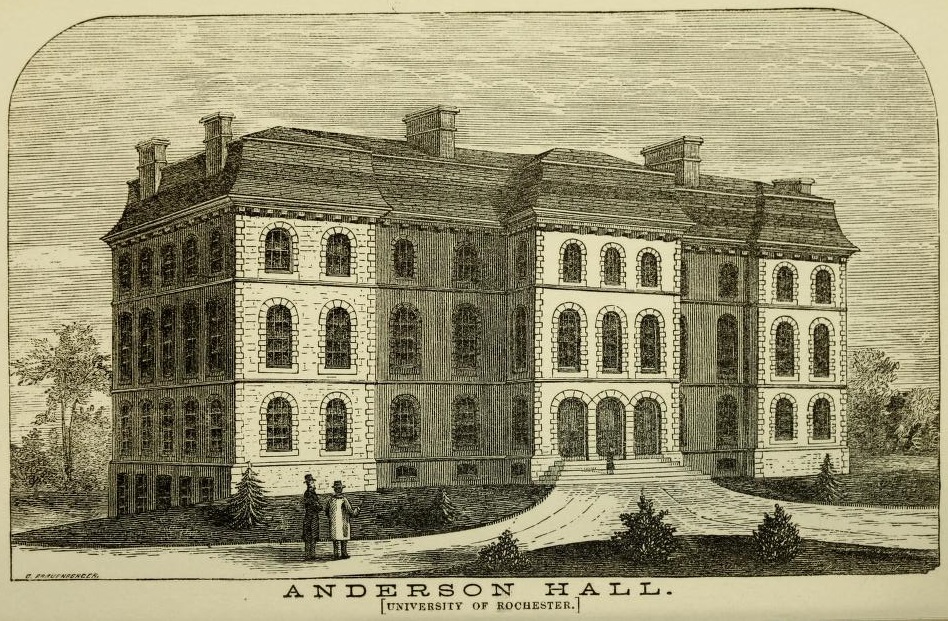

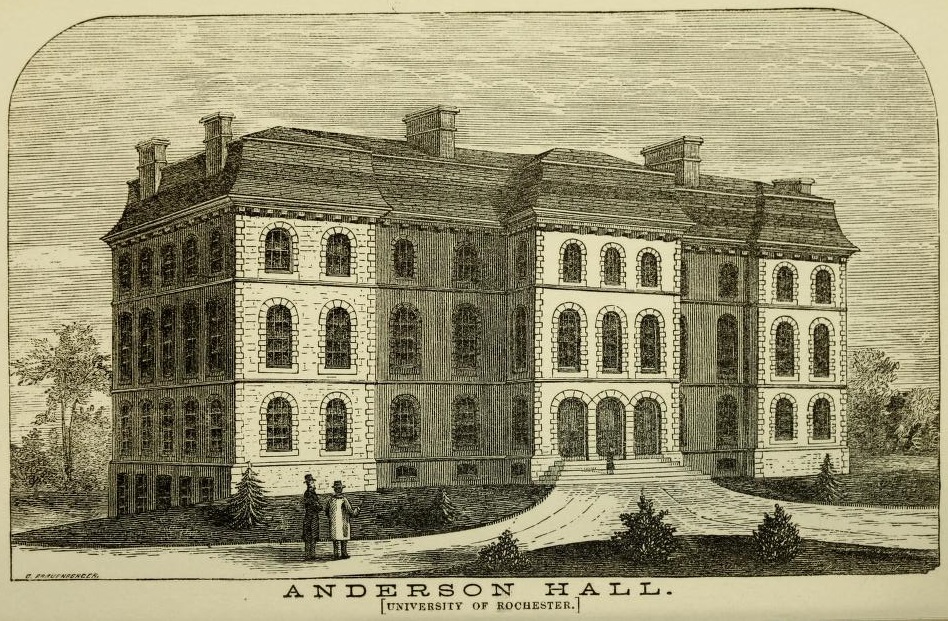

| Prince Street Campus | Anderson Hall |

|

| Anderson Hall, from Twelfth Annual Catalogue of the Officers and Students of the University of Rochester, 1861-2. |

Anderson Hall was the first building erected on the Prince Street campus. It was sold after the College for Women moved to the River Campus in 1955 and now houses the United Way of Greater Rochester.

References

1859 "Contract for construction of new buildings awarded to R. Gorsline

& Son and Edwin Taylor," Rochester Union and Advertiser,

October 1, 1859, Page 2-3.

1861 Anderson Hall first occupied.July 9, 1861 1891 regents report

1861 "Dedicatory exercises of the University of Rochester," Rochester Union and Advertiser, November 25, 1861, Page 2.

1910 The

University of Rochester : buildings and grounds

Page 8: Anderson Hall. Built in 1861. Of brown

sandstone. Contains the chapel, lecture rooms, and administration

offices.

1931 "A Tour of Inspection in Anderson Hall," Rochester Review 9(3):75-77 (February-March 1931)

1955 "University

Sells 2 More Buildings at Prince Street," Democrat and Chronicle,

December 2, 1955, Page 37.

Anderson Hall sold to Dr. Aldolph F. Bastian for a general office

building. Also 15 Prince Street.

1977 History

of the University of Rochester, 1850-1962, by Arthur J.

May. Expanded edition with notes

Chapter 6: A Critical Decade

Before state financial aid was assured, the University managers started to

lay plans for an educational structure on the Boody tract. Anderson kept

complaining that bigger classes and the inadequacy of library facilities

made a new building imperative, yet he was unwilling to incur debt for the

purpose. He devoutly wished that a wealthy friend of the University would

"feel disposed to make his name immortal" by financing the cost of a

building in return for having his name attached to it. Certain trustees

and students chafed over the delay in getting construction underway, one

undergraduate drily commenting, "... the [Prince Street] grounds afford

pasturage for cattle on a thousand hills and fields for the exercise of

the various Ball-Clubs."

The money made available by the state and basic architectural philosophy

determined the character of the proposed structure, since it was reasoned

that "large or elegant edifices do not make an efficient institution of

learning." The President inspected the Yale and Harvard campuses and

conferred with professors at both places in order to get first-hand

impressions on the best in academic architecture and internal layout. By

July of 1859 planning had sufficiently matured to warrant the appointment

of a joint trustee-faculty committee to scrutinize designs in terms of

economy and convenience. Two main sets of blueprints were seriously

examined and lively controversy ensued, for opinions differed on which of

the two was preferable. On September 14, 1859, however, a majority

of the committee voted for a design prepared by a Boston architect,

Alexander R. Esty, who would be compensated with a fee of five percent of

the cost of construction. Contracts were awarded to Richard Gorsline and

Son--a firm responsible for several major public buildings and private

residences in Rochester--for the stone and brick work, and to Edwin Taylor

for the wood and slate work.

The building, eighty by a hundred and fifty feet in dimensions, was

erected on the northern edge of the university park. The facade had three

stories, while a basement gave the north side the appearance of four

stories. The roof reflected the mansard tradition and dormer windows

admitted light into attic quarters; the design permitted the addition of

another floor, should it ever be needed. For the outer walls, plain brown

stone, called "Medina Sandstone," quarried not far from Rochester, was

used; it was reputed to be as durable as the finest product of New England

quarries

Except for kerosene lamps in the basement dwelling of the janitor, rooms

were not equipped for artificial illumination, so they could not be, used

at night. Heat was supplied by one or two large wood-burning stoves in

each room; fuel, stored in the cellar, was hauled from room to room on a

wheeled cart. Smoke issued from tall chimneys on the roof, which stood

unaltered until 1929-1930 when the Hall was completely reconstructed.

Construction of the new University home proceeded at an exasperatingly

slow pace, but in the autumn of 1861 it was ready at last for occupancy.

Sewers were laid down and a bog in front of the building was eliminated by

a drain that removed water from a spring; much of the rest of the property

remained woodland and hay fields and a wooden fence surrounded the campus.

Owing to the outbreak of the Civil War, no formal dedication of the

building took place. Instead, on Saturday, November 23, 1861, modest

inaugural rites were conducted in the chapel. The President followed along

with the history of the building and its financing, alluding to "the days

and nights of depression, anxiety, and exhausting care" he had experienced

in bringing the structure into existence. "This internal history will

never be written," he said, "It is best that it should be forgotten."

Answering critics of the sober architecture, he acknowledged that

"somewhat practical and unartistic conditions" and slight mistakes had

entered into the construction.

Chapter 8, Continuity and Growth

Expansion of campus facilities, crowned by the erection of Sibley Hall,

and beautification of grounds moved modestly ahead. To heat rooms in

Anderson Hall, coal replaced (1869) wood as fuel, but student complaints

of insufficient warmth in the rigorous months of winter were common. "The

stoves in the chapel are very ornamental, but a little fire every morning

would add to comfort," an undergraduate wryly observed. After the

President had devoted a chapel talk to the health hazards of cold weather,

the students repaired, we are told, to a "fireless recitation room." In a

fiery letter to the Campus, an undergraduate blamed the janitor for

failure to keep rooms warm and recommended that unless he bettered his

ways he should be discharged; "My feet are cold, but my indignation is

hot," and the writer signed himself "Yours freezingly."

© 2021 Morris A. Pierce